In the 1970s, archaeologists began to question the appearance of strange symbols and curious caches of objects on sites occupied by enslaved Africans. The Garrison Plantation (18th -mid-19th century), near Baltimore, was one of the first sites in Maryland where indigenous magic was recognized by archaeologists. Here, spoons decorated with herringbone lines and geometric shapes were found within the slave quarter.

Soon after, University of Maryland students began to find collections of glass, buttons, and bones secreted under the floors of the homes of elite Annapolitans. They even found a clay mass containing a stone axe with straight pins, lead shot, and bent nails, four feet under a street. The association with the metal and stone axe brought some to believe it may be associated with Yoruba and the Fon people of Benin, who considered the axe blade a symbol of Shango, their god of thunder and lightning.

Archaeologists have interpreted these odd scratches and collections of otherwise prosaic items in curious contexts as African spirit practices. Sometimes called hoodoo, folk magic, or root work, this belief system was brought from Africa and carried out in secret. In creative attempts to hide this knowledge and preserve their beliefs, African Americans began to incorporate Christian images into their practice. The incorporation of such symbols and saints within their practice is not assimilation or creolizing of an African religion. Instead, the use of these familiar symbols allowed West African spirit practices to be displayed in public and without consequence.

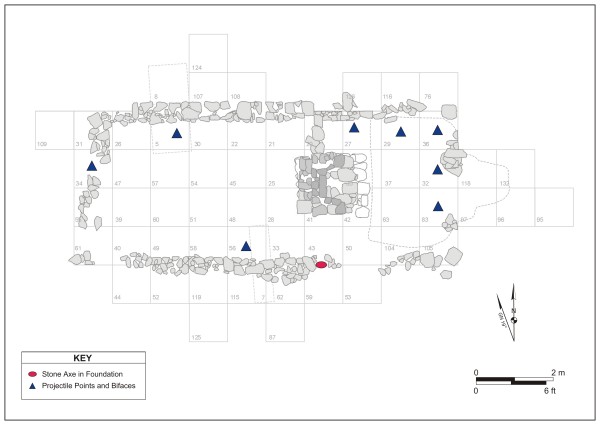

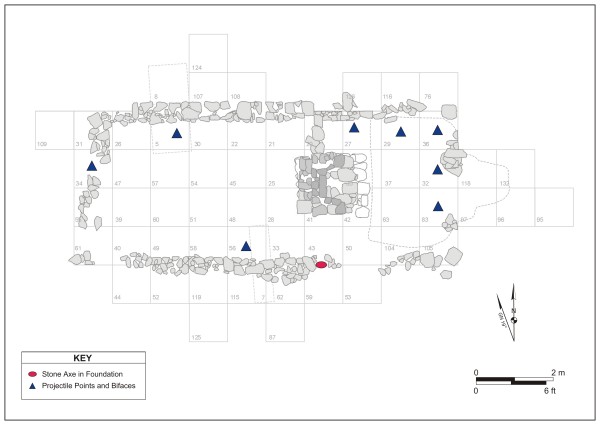

At the Jackson Homestead (1840-1920) in Montgomery County, we found objects and caches tucked in and under the home. At least three methods to protect the Jacksons’ home were interpreted from the artifact assemblage and its tight context, including a Catholic Infant of Prague medallion. Prehistoric artifacts were found in an interesting arrangement surrounding the foundation. Eight quartzite projectile points were placed around the foundation. In another instance, a stone axe was tucked in the southwest corner of the original slave cabin. Like the find under an Annapolis street, the stone axe may be another connection to Shango

|

The recognition of these spirit practices in archaeological sites is exciting since it provides a template and an awareness to help us recognize Africa in Maryland. Just as important is the ability to know when this cultural expression is not present. Archaeologists working on the Belvoir Slave Quarter (1780s-1870) in Anne Arundel County, for example, did not find evidence of African spirit practices. It is possible this home’s nearness to the manor house dissuaded the enslaved community to practice at the quarter; or they simply may not have adhered to these African beliefs. |

Julie M. Schablitsky

Maryland Department of Transportation