| |

Another way is to stop the urine of the Patient, close up in a bottle, and put into it three nails, pins, or needles, with a little white salt, keeping the urine always warm: if you let it remain long in the bottle, it will endanger the witches life: for I have found by experience that they will be grievously tormented making their water with great difficulty, if any at all…The reason…is because there is part of the vital spirit of the Witch in it, for such is the subtlety of the Devil, that he will not suffer the Witch to infuse any poysonous matter into the body of a man or beast, without some of the Witches blood mingled with it…”

Instructions on how to make a witch bottle from the Astrological Practice of Physick by Astrologist Joseph Blagrave, published in London, England in 1671. |

|

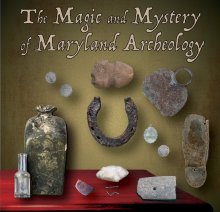

In early modern England, as well as in the British colonies, the belief in a “witch” as inherently evil and a tool of the Devil was widespread. The Christian church’s focus on salvation from the evil forces of “devilry” fostered this belief. The daily struggles of human life were seen as a direct result of the great cosmic battle between God and the Devil, with the witch as one of the Devil’s primary weapons. Communities felt compelled to identify the witches in their midst and to find ways to protect themselves from their malevolent intentions. Outbreaks of witchcraft hysteria and subsequent mass executions began to appear across Europe and America. Individuals turned to ritual magic to counter witch’s curses or to ward off evil spirits from their homes. Evidence of these magical charms in the form of “witch bottles” have been found on archaeological sites throughout England and America, with five known examples in the state of Maryland’s archaeological collections

While there are variations, most witch bottles were made by filling a glass bottle or ceramic jug with urine, human hair and/or nail clippings, animal bone, and sharp objects, such as nails or pins. The bottle was then buried inverted by the entrance to a home or under a hearth. When created as a counter-curse, the placement of sharp objects in the victim’s urine was believed to turn the curse back on the witch, making the witch unable to urinate, and ultimately leading to the witch’s demise. Inverting the bottle when buried also symbolized the reversing of the witch’s magic. While it is impossible to know the true intent behind the creation of any specific witch bottle, many may have simple been preemptive protective charms rather than a counter-curse directed at an individual witch. |

|

The two examples of witch bottles from 17th-century sites in Maryland are both represented by multiple bottle burials. The remains of four case bottles were found in a small pit near a possible chimney or entranceway to an earthfast house at the Patuxent Point site in Calvert County. Three corroded nail fragments, a pig’s pelvic bone, and the lower jaw of a small mammal were also recovered. All four bottles were broken; however, it appeared that they all went into the ground intact, indicating an intentional burial. At the Addison Plantation site in Prince George’s County, three wine bottles were found buried together at the top of the passageway leading from the cellar of a structure similar to the one at Patuxent Point. While no additional artifacts were recovered, the burial location and the inverted position of the bottles support the identification of these as a possible protective charm.

An example of an 18th-century witch bottle burial was found at the White Oak site in Dorchester County. A wine bottle neck, horseshoe, bottle glass sherds, and bone fragments were recovered by a brick hearth. Several straight and bent pins had been inserted into a solid stopper in the bottle neck, both on the inside and outside of the bottle. The horseshoe may have also been associated with the ritual burial, as iron in any form holds its own protective powers

|

The two examples of possible witch bottles from 19th-century contexts in Maryland were not made from wine bottles but from redware ceramic jars. These may represent an evolution of the traditional witch bottle into a good luck “bottle charm”. One was a redware ceramic vessel found buried with a horseshoe below a hearth in a house in Fells Point in Baltimore City. The location of the jar and the horseshoe indicates that this ritual burial may have played a similar role to witch bottles found on the colonial sites in Maryland. A similar but slightly smaller ceramic jar was found buried in the southeasternmost corner of the brick manor house cellar at the Addison Plantation site. No other artifacts were recovered, so it is possible this vessel was simply used for storage. However, its similarity to the vessel from Fells Point is intriguing. |

These witch bottles and bottle charms are clear evidence that folk magic, deeply rooted in European traditions, was alive and well, not just in the early years of the colonies, but well into the 19th century. While such efforts may seem amusing to us in the 21st century, these magical objects represent sincere efforts by individuals to protect themselves from what were perceived as very real threats from the supernatural world.

Rebecca Morehouse

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory

|